Swimming 101: The Beginner's Guide to Swimming

In This Article

This is the ultimate guide to learning more about swimming and was created for anyone looking to learn more about the sport. After reading this, you may not be an Olympian but you will have the foundation to start your own swimming journey. We touch on lingo, equipment, stroke technique, types of events, and everything in between.

This is a high-level crash course broken into four parts. We recommend you start with The Basics and work your way through The Stroke Basics, Adult Swim Training, and Events 101. However, you can jump around to what is most relevant to you. Enjoy!

The Basics is part one of our four-part Swimming 101 guide. The other three parts are linked below when you're ready for them.

There are lots of ways to propel yourself through water. Dog paddle, sidestroke, and double-arm backstroke come to mind when thinking of recreational strokes that you might see at the pool.

Although all those are good for fitness, adult swimmers generally get the best workout by using the four competitive strokes: the long-axis strokes of freestyle and backstroke and the short-axis strokes of breaststroke and butterfly.

The long-axis strokes are so named because much of the movements are centered around the vertical line of your body and rotation around that axis (think top of your head straight down through your feet). Similarly, the short-axis strokes focus movements through the horizontal axis of your body (think horizontally through your lower ribcage).

All four strokes have positions and movements critical to helping you move through the water with the greatest velocity and the least amount of effort. Here’s an overview of each stroke and its basic elements.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

Freestyle races technically can be swum using any stroke, but the front crawl stroke is the fastest of the competitive strokes and it’s become synonymous with freestyle. Here are the basic elements of how to swim effective freestyle.

Body Position

Keeping a good horizontal position on the water is a key element of effective freestyle. The basic position is horizontal on the water with your head, hips, feet, and hands all at the surface of the water. As you remain stretched out on the water, make sure your face is in the water and you’re looking straight down, or at a slight angle forward, at the bottom of the pool.

Arms

A good freestyle arm stroke consists of four basic elements that provide the bulk of the propulsive force for swimming.

- The catch. Once your hand enters the water, pitch your fingers down so that your hand is perpendicular to the direction you want to go. As your hand pitches down, rotate your elbow and shoulder so that your forearm is also perpendicular to the direction you want to go.

- The pull. During this part of the stroke, pull your arm through so that your hand and forearm stay perpendicular to the direction you’re going and your elbow remains bent.

- The finish. Once your arm is about midway down your body, transition from a pulling motion to that of a pushing motion, almost as if you’re going to try to slap your thigh with your hand.

- The recovery. Raise your arm out of the water, almost as if pulling your hand out of your pocket, and bring it back to the front position where you started by sliding your hand fingers first into the water 8 to 10 inches in front of your head and extending your arm fully after that.

Legs

Flutter kick should be done in a relaxed manner with small amplitude. Keep your ankles loose and your heels just below the surface. Experiment with how big you make your kicks, noting that the higher the amplitude, the harder it is and the more drag you produce. Ideally, you should feel the water roll down your legs and off your toes.

Breathing and Rotation

As you’re alternating your arms, your body should be rotating gently. It’s very difficult to swim and breathe if you try to stay flat on the water. In freestyle, breathing is to the side. You use your core muscles to rotate your body side to side, so you won’t have to strain your neck, look, or twist to breathe. Make your breathing as rhythmic as possible. Exhale slowly when your face is in the water and let the air fall into your lungs when you inhale.

Backstroke is like freestyle in the sense that body position and rotation are foundations for doing it well, but there are differences, the most obvious being that you swim on your back.

Body Position

Even though you can breathe more easily because your face is out of the water, your rotation is even more pronounced in backstroke. Also tilt your pelvis up and keep your toes at the top of the water, as though you’re doing a small crunch, drawing your belly button to your spine.

Arms

A good stroke is different than a freestyle one, but it has the same basic elements. An effective way to visualize this sequence is to think of grabbing water and throwing it toward your feet.

- The catch. Rotate your hand so that you pitch your pinky toward the bottom of the pool. This will cause you to rotate onto your side slightly. At this point, flex your wrist so that your hand is perpendicular to the direction you wish to go.

- The pull. Bend your elbow so that your forearm is also perpendicular to the direction you want to go. It’s good to keep your elbow away from your body and prevent your elbow from leading the pull. Pull your arm through so that your hand and forearm stay perpendicular to the direction you’re going and your elbow remains bent.

- The finish. Once your arm is about midway down your body, transition from a pulling motion to a pushing motion, almost as if you were going to try to slap your thigh with your hand. Finish your stroke with your palm toward your body rather than the bottom of the pool.

- The recovery. With your hand at your thigh, raise your arm out of the water, almost as if pointing your fingers straight up to the ceiling or sky. Your thumb will exit first, and your arm should remain straight and as vertical as possible. Somewhere near vertical, it rotate your hand so your pinky leads the recovery. Enter pinky-first, shoulder-width or slightly wider apart to be ready for the next catch.

Legs

As with freestyle, you shouldn’t have a big, splashy kick. The up-kick is important, so think like you’re flicking your toes at the top of the water. Use your whole leg and if you find your feet sinking, adjust your body position by rotating your pelvis up to get your feet up.

Breathing and Rotation

Your face is out of the water on this stroke, so you get to breathe when you want. It’s good practice to breathe in through your mouth and out through your nose just in case you splash water into your face. Rotation is key: Finish your pull well and use your hips to rotate your stroke, and you’ll be less likely to drip water onto your face.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

Breaststroke is the most complex stroke, and it’s difficult to do well. Everyone can learn to swim this stroke, but the natural rhythm and timing come more easily to some than others. It’s a great stroke to learn if you swim in open water because you get to breathe every stroke and see where you’re going. Your body position is also critical here, but the propulsive forces are different.

Legs

People sometimes call this the frog kick because it does seem to mimic what a frog might do, but the correct term is now whip kick. To do whip kick, draw your heels up toward your hips. Once your heels are close to your hips, rotate your toes and heels out so they’re wider than your knees and sweep them together. Your lower leg and foot should be dorsi-flexed, or in an ‘L’ position. You’re pushing water back with the inner side of your feet. Squeeze your ankles together and point your toes while finishing your kick. Remember these motions are more about pressure than speed or strength.

Arms

The second propulsive element of breaststroke is the pull. Unlike freestyle and backstroke, your kick and pull are independent of one another, and timing is the key.

To focus on a good breaststroke catch and pull, lay in the neutral position on your front. Extend your arms with your palms down in almost a streamline position without stacking your hands. The catch movement is initiated by sweeping your hands out slightly past your shoulders while pitching your fingers down toward the bottom. Your torso and arms should almost make a “Y” when viewed from above.

As your fingers pitch down, your elbows will bend slightly to get your forearms into a more vertical position and put additional pressure on the water. Then bring your elbows together under your body while simultaneously moving your hands forward. Bring your hands together and imagine you’re pushing a needle forward with your hands. An effective trick for thinking about these movements together is to imagine that you are scraping cake batter out of a bowl with your little fingers and then pushing it to someone else. Your hands accelerate throughout your catch and pull phase until reaching the neutral position again. It’s very important that your hands never go farther down your body than your shoulders.

Timing

One of the advantages of breaststroke is that you get to breathe every stroke. The exact timing of this breath is an important part of the rhythm of the stroke.

Start your breath as you sweep out with your hands. Use the out-sweep to generate lift so all that’s needed is a simple push of your chin forward. Remember to breathe out while your face is in the water. With the other pressures on the water, this should be sufficient to get your mouth and nose out of the water. Some swimmers will rise higher in the water than others. Find what works best for you.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

Butterfly, the other short-axis stroke, grew out of breaststroke and is often thought of as the most difficult stroke to master. Both short-axis strokes are all about the rhythm and timing. Although it’s true that you rotate on a shorter axis (through your chest rather than down your spine) the most important concepts to keep in mind are common to all strokes.

Stroke and Timing

The basic motion of butterfly is an undulating rhythm with your legs and arms synchronized at just the right time. The most important element of good butterfly is proper use of your core.

While on your stomach with your arms stretched in front of your shoulders, press your chest down to initiate your undulation. Perform a downward motion with your feet with your legs together (the down-beat of your dolphin kick) to help accomplish this. Then push your hips down while arching your back to bring your head and chest back toward the surface. You should feel some pressure on the backs of your legs and bottoms of your feet as you bring your feet back to the surface (the up-beat of your dolphin kick). Use the dolphin kick to provide propulsive force and manipulate your center of buoyancy to produce an undulating motion.

As you complete the undulating and kicking motion, pitch your fingers down to the bottom of the pool and bend at your elbows in a motion like pressing yourself up out of the pool at the end of a workout. Once your hands and forearms are close to vertical, push back while accelerating them. Push your chin forward slightly, and the propulsive force of your hands and forearms will cause your face to rise out of the water high enough to get a breath.

Accelerate your hands past your hips and out of the water. With your head and shoulders out of the water, a forceful movement of your hands at the finish will allow you to recover your arms in a straight fashion over and parallel to the surface of the water. The entry of your hands and arms should be above your head in front of your shoulder, if not a little wider, to return to the start position for your next stroke cycle.

Rhythm and Breathing

Just as in breaststroke, start your breath early in your pull. The feeling should be a wave-like flow. If you mess up your timing, butterfly gets really exhausting. Make it easier by adding fins while you’re learning.

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

Good question! Swimming all the strokes is the best way to get a great core workout and develop muscles that promote shoulder health and stability. It’s also a great workout for your mind because learning new things is challenging and rewarding. Learn all the stokes and you’ll never have to swim mindless lengths of freestyle again.

—SCOTT BAY

When you start swimming with a Masters group, you know to bring a suit, a pair of goggles, a cap, and a towel. But there are some other pieces of basic training equipment that will both enhance your training and help your swimming evolve.

Some stuff is great to get right away, other stuff you can wait until you’ve been swimming longer. Here’s a list of the basic items that most programs use and why they help or enhance your training, as well as how you can care for it.

Things Great for Newbies

If you look around at the bags on the pool deck of any Masters workout, you’ll notice a variety of equipment in a bunch of different shapes, sizes, and designs. Many of these items have been acquired by swimmers over years of swimming. If you’re just starting out, keep it simple and use things that will help your technique:

- Fins. These are a staple for a lot of Masters programs and for good reason. First, they provide extra resistance when you’re kicking. This helps strengthen your kick, which requires more than having strong legs as many Masters swimmers who come from a running or cycling background have discovered. You’ll also notice a variety of blade lengths and designs. A medium-blade fin with maybe 6 to 8 inches past the toe is a good place to start. Too long may cause poor technique and damage to your ankle, especially if you lack flexibility in that area. Fins that are short do have a purpose, but if your goal is extra propulsion, skill acquisition, and strength building, it’s best to start off with the medium fin.

- Pull buoy. These little foam devices, placed between your thighs while swimming so you don’t kick, allow your hips to float without the buoyancy brought on by your kick. There are several reasons for using one but for most, it allows you to focus on just the pulling motion rather than pulling and kicking at the same time. These are great for setting up an effective catch while eliminating that sinking feeling when you slow down your stroke rate to focus on your technique. There are lots of different designs out there, but they all have the same basic function.

- Swimmers snorkel. These are centered in front of your face with a bracket on your forehead, rather than off to the side of your head and attached to a mask as regular snorkels are. They’re awesome because you can leave your face in the water and concentrate on your stroke without worrying about needing to turn or lift your head to breathe. A snorkel allows you to isolate just one skill to work on while staying aerobic. It’s also great to reduce any back or neck strain you might be feeling if you have old injuries or are still learning proper technique.

Things To Get Later On

While you were looking around at bags on the pool deck, you probably noticed a bunch of other equipment in other swimmers’ bags. Some of it may be a good idea depending on what you’re doing but not necessary to get started.

- Kickboard. Most would put this in the basic category of equipment, and many facilities have them available for use. Not all swimmers should use them, though, because laying your arms on the board, craning your neck up, and arching your back can cause some discomfort and throw your swimming posture off. There is a benefit, however, to having the ability to be in the head-up position to kick, especially when working on breaststroke kick. To alleviate neck issues, you can kick with the board extended and your face in the water while using your snorkel.

- Hand paddles. Here again, there are lots of shapes and sizes. In this case, size matters a lot. The shoulder is a complex joint, supported by large and small muscles. Paddles add extra resistance and over time using paddles can cause damage to the smaller shoulder muscles. These muscles are not like fingernails—they don’t grow back after you damage them. Start with small paddles until you build skill and strength, then try larger sizes if you wish. It’s important to remember that this is only helpful if you already have good technique.

- Ankle strap. These are typically used with a pull buoy and keep your feet and legs together, so you don’t have to squeeze your thighs to keep the pull buoy in place. It’s impossible to kick while wearing one, so that tendency to kick with your pull buoy is eliminated. An ankle strap is great for working on alignment and using your core for rotation rather than your feet.

Care of Your Equipment

The good news is that most of your swimming equipment is reasonably priced, but why replace it more often than necessary? Here are a couple of tips to help prolong the life of your equipment.

- Rinse. Rinse your equipment in fresh, cool water after each use to remove chlorine and salt, both of which are corrosive. Manufacturers may also include other care instructions on the product packaging or on their website.

- Store. Many swimmers who swim in the morning leave their equipment bags in their cars during their workday. Temperature extremes can wreak havoc on your equipment, from dry rot to mildew growth, so if you live somewhere with extreme heat or cold, try not to leave your equipment in the car.

- Wash. Again, this is where you should follow manufacturers' instructions, but cleaning with a mild detergent from time to time is a good idea. USMS partners with swim equipment manufacturers and vendors such as SwimOutlet.com that offer discounts for USMS members throughout the year. Before you start adding to your online cart, however, check with your fellow swimmers and your coach. They may have some recommendations and suggestions for you and often will let you try out their equipment to see if you like it. Your equipment should match your ability, experience, and goals. Some of this is important to your development as a swimmer, and some simply a matter of preference.

—SCOTT BAY

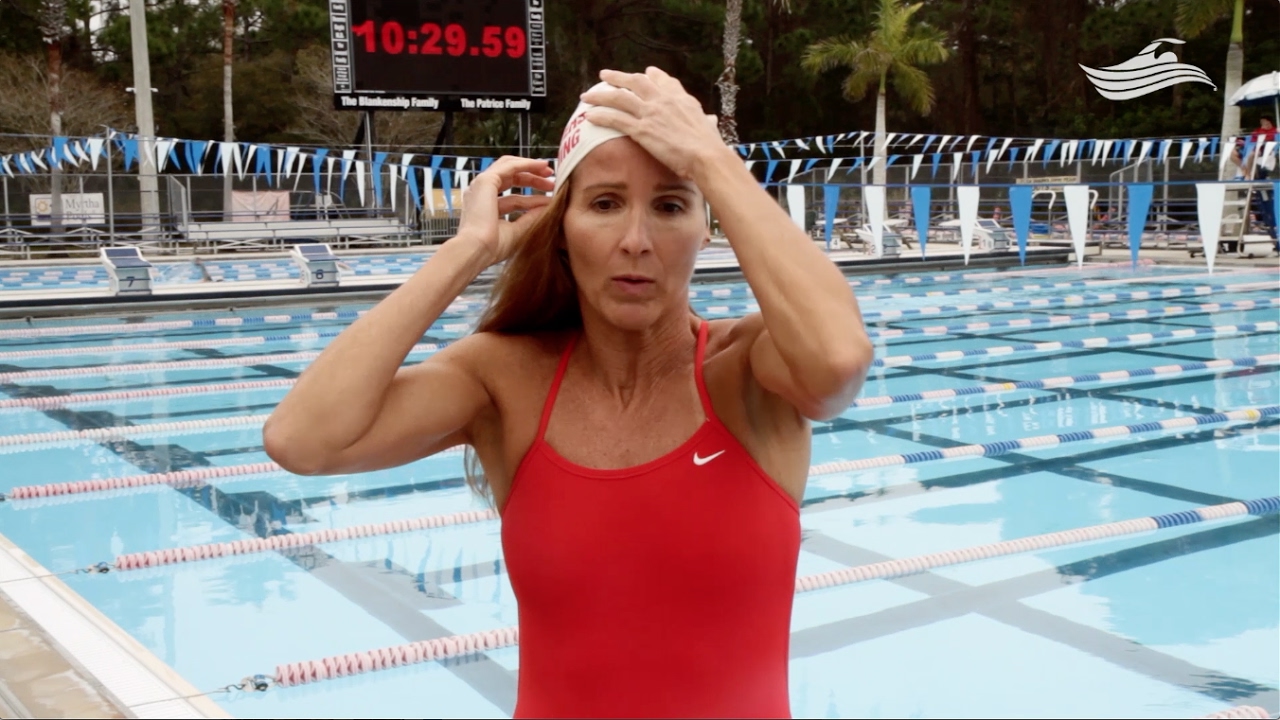

When you’re starting out as a Masters swimmer, there are a few items essential for getting the most out of your swimming experience: a swim cap, a pair of goggles, and a swimsuit.

The common theme for all of these is making sure each one fits correctly and that you wear them correctly for both comfort reasons and to reduce drag.

Here are some tips for selecting what’s right for you, as well as some tips for putting on and taking off each item.

Swim Caps

Swim caps for competitive swimming are usually either latex or silicone. Lycra caps are also used, especially in warmer climates and in open water, but they don’t offer any protection from chlorine or salt water and they aren’t very hydrodynamic, though they’re more comfortable.

Latex caps are thinner than silicone, making them a little cooler, a little more prone to tearing but also cheaper. Silicone caps are thicker, warmer, more hydrodynamic, and are easier to care for. They’re also more expensive.

Regardless of which you choose, putting either on is relatively the same. For extra protection from chlorine, wet your hair with fresh water before you put your cap on. Most caps are one-size-fits-all, but some come larger for swimmers with longer hair.

- On your own. The seam always goes from the middle of your forehead to the nape of your neck. Many new caps come with instructions for putting them on. The one that typically comes with each cap is the two-hand method. To do this, you insert your hands, palms together, into the cap and then separate your hands to stretch the cap and place it over your head. This is great if you have short hair or your longer hair is tied up in a way that makes this easy. You can also stuff your longer hair up inside once the cap is on by dividing it into two hunks at the nape of your neck and then stuffing them up above your ears.

- Cap me, please. This effective method is popular with athletes with longer hair or a lot of hair. Find a teammate to take the back edge of your cap while you hold on to the front edge, keeping it at your forehead. Lean forward slightly and hang on to the front of the cap while your friend quickly stretches the cap over the back of your head to your neck.

Goggles

There are many styles of swim goggles, and fitting yours to the shape of your face is the most important point when purchasing a set. To figure out your fit, you first must know how to put them on.

- Eyes first. Place the eyepieces on first and stretch the strap behind your head. Position the strap slightly lower than the top of your head. If your goggles have split straps (many do), you can position one strap above a lump of hair and one below. Whatever feels secure and keeps your goggles fitted properly around your eyes is best. The eyepieces should be below the bony part of your eye sockets, so they rest on soft tissue rather than bone or eyebrows.

- Back to front. Position the strap around the back of your head and then lower your goggles into place over your eyes. This method can cause you to make multiple adjustments because the most important aspect—the fit around your eyes—didn’t come first.

Fit is the most critical part of a pair of goggles. Ideally, you should be able to gently press the eyepieces around your eyes and have them stay there just on the seal between your skin and the goggle. The strap is just there to hold them in place. Shapes and sizes of faces and ocular orbits vary greatly, so find goggles that fit properly.

Suits

Over time, training and racing suits have run the gamut from maximal to minimal coverage and ranged from wool to neoprene and many fabrics in between. If you’re just starting in Masters swimming, the only suit you need for now is a well-fitting training suit.

- Training suits. These are typically made of durable fabrics such as a polyester and Lycra blend. The more Lycra, the softer but less durable the suit will be. These fabrics aren’t very hydrodynamic because the porous fabric produces drag. But they last a long time and are perfect for training.

- Racing suits. Made of high-tech hydrodynamic fabrics and often requiring assistance in donning because they need to be super tight, racing suits are expensive and not very durable. They can, however, help you eke the most out of your training when you go to race.

Putting on a training suit is easy, but the fit should be snug. Too big and you end up with a bunch of drag. Too small and you end up with discomfort from chafing. Suits should be snug when they’re new, and stretch to a snug-but-comfortable fit when they’re broken in. You should feel like you’re being firmly hugged by the suit but not constricted. Brands will have different sizing guides so, if possible, try them on first.

Pro Tips

Try things on to get the best fit. Caps are cheap, so a few to buy and try is fine. Goggles and suits aren’t as cheap, but unless you have a well-stocked sporting goods store or a specialty store catering to swimmers or triathletes, it will be hard to try them on before buying. Check online retailers’ return policies and proceed accordingly.

You can also try to find a large swim meet being held in your area, such as one hosted by a local age-group team or Masters club. Often these meets have vendors set up with products for swimmers to purchase.

—SCOTT BAY

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

The decision to become a Masters swimmer changes your life for the better in myriad ways. Not only does it set you on a path toward a longer life with better health and fitness, but it also introduces you to new friends and engaging activities that enrich your life in ways you didn’t anticipate.

But when you first walk onto a pool deck as a Masters newbie, you’ll notice things you ignored before. Here are some of the elements you’ll encounter at a typical pool that accommodates Masters workouts and swim meets.

The Pool

Although many aquatic facilities have multiple pools (potentially including diving wells, therapy pools, hot tubs, etc.), this article addresses your generic training pool that can also be used for racing. We can’t cover all possible variants, so explore your facility and get to know its features.

Standard short-course competitive pool length is 25 yards in the U.S. There are some 25-meter pools (about 7 feet per length longer than 25 yards), which is standard overseas. Long-course (sometimes called Olympic-sized) pools are 50 meters long. Many pools are set up to be changeable with the seasons, which varies, but summer months are often long course, with short course meters at some point in the fall, and the rest of the year short course yards.

- Lane markings. Each pool is divided into lanes that feature a painted or tile stripe that runs down the center of the lane. These lane stripes have a crossbar (known as the “T,” or turn warning) a couple of feet from the wall. This crossbar lets you know, without having to lift your head to look, that the wall is imminent. Multi-purpose pools may also have additional stripes for different course setups. The wall at each end of the lane also features a plus-shaped cross that provides a reference for depth perception and foot placement for push-offs. During competitions, a thin touchpad can be mounted on the wall to sense the swimmer’s turns and finish for the electronic timing system. Touchpads typically cover the built-in wall cross markings with a non-skid surface that has its own cross-shaped mark.

-

Lane lines. Lanes are separated by a series of round perforated plastic disks held in place by a wire anchored to each end of the pool. Older folk like me may refer to these as “lane ropes” since the original lane separators were actual ropes until the middle of the 20th century. Lane lines help swimmers stay in their lane and reduce waves.

Alternating colored sections of disks help the swimmer gauge speed and distance, with a longer section of a single color, beginning at the backstroke flags (see below), to indicate the final approach to the wall. There are also uniquely colored disks at 15 meters from each wall to indicate the maximum legal distance a swimmer can stay underwater for butterfly, backstroke, and freestyle races. - Backstroke flags. Because backstrokers are looking up, they can’t see the markings on the bottom. To help them anticipate approaching the wall, a cable with triangular pennants is suspended across all swim lanes, near both ends of the pool. In a yards pool, they’re 5 yards from each end. In a meters pool, they’re 5 meters. In long-course pools, there will also be a single unflagged line suspended over the center of the pool to indicate the half-length point.

- Pace clocks. Workout sets often feature specified time intervals and target swim times that require a timing system to help the athletes and coaches keep track. Pace clocks display minutes and seconds either with sweep hands (analog) or large lighted numerals (digital) that should be visible from every lane.

- Workout communication. Depending on the facility and coaching staff, workouts may be communicated to swimmers through methods that include writing on a white board or digital display (such as a lighted scoreboard), through printed sheets distributed to each lane, or delivered orally by a couch with a loud voice (or microphone), etc. If you have any problems understanding the workout, ask the coach for detailed instructions.

- Circulation system. Water in competition pools is between 77 and 82 degrees, but multi-purpose pools may be warmer to accommodate water aerobics and lap swimmers. Because pool water must constantly be cleaned and treated, you’ll notice drains, water jets, and overflow gutters that help circulate the water through heaters and filters, etc. Pay attention to the gutter configuration to avoid tripping and toe-stubbing hazards.

- Bulkheads. Some longer pools have moveable walls called bulkheads that can be used to change the length of the competition area, such as dividing a 50-meter pool into two 25-yard courses.

- Starting blocks. The raised tilted platforms at the end of each lane are called starting blocks. Diving from this additional height can help competing swimmers achieve more velocity at the start of the race. (Note: No one is required to start from the blocks; it’s perfectly legal to start from the edge of the pool deck or even from in the water.) The top surface of the blocks should have a grippy surface so wet feet can’t slip, and may offer an optional adjustable wedge to support the trailing foot for those who use a track start (one foot forward and one back). Hand grip bars for in-water starts are attached below the platform for use in backstroke events, and optional retractable foot ledges may be offered for underwater foot support for backstroke starts. Starting blocks should only be used by those who have been trained to use them safely. They are usually off limits to everyone except during coached workouts and officiated competitions.

- Entry and exit options. Most competition pools offer multiple points of access to the water, including options such as stairs, ramps, ladders, and hydraulic lift chairs for those with mobility issues. Use caution and common sense when entering or exiting the pool, asking permission to enter as appropriate and performing a visual scan of your entry point to ensure that you won’t affect or interfere with other swimmers in any way. At USMS events during warm-up, all entries must be done feet first (with the exception of designated lanes for start practice), and this is a good rule of thumb to follow at all times.

The Facility

The first thing you should do when entering an aquatic facility is to familiarize yourself with the pool infrastructure as well as etiquette, safety protocols, and emergency considerations. These include:

- Posted signage and rules. Most rules are obvious (no running or horseplay, no diving into shallow water, no glass on deck, etc.) but each facility may have additional restrictions appropriate for local conditions. Obey all posted rules, and if you have questions, ask a staff member.

- Lifeguards. Pool safety staff are trained to recognize potential hazards and to respond to emergencies, so follow their instructions without hesitation. Do not distract or disturb on-duty lifeguards, so they can do their best to keep everyone safe.

- Safety equipment. While the use of safety equipment is the sole responsibility of the lifeguards, it pays to familiarize yourself with the location of key components in case a staff member requires assistance during an emergency. Such elements include phones, the posted address of the facility (to provide to emergency services dispatchers), automated external defibrillator, emergency exits, etc.

Although it may not be a requirement at your pool, it’s always a good idea to have a personalized medical emergency card in a waterproof sleeve with your on-deck gear. It should feature a recent photo, an emergency contact, and any medical conditions, medications, allergies, etc., that could provide information for emergency service providers if you become incapacitated. - Necessities and amenities. Locate the appropriate restrooms, showers, lockers, etc. There should also be drinking fountains or places to fill water bottles. Lockers may or may not be rented, reserved for swim teams, or open to the public if you bring your own lock. If you have special needs, talk to your coach or facility staff to arrange accommodation.

- Swim equipment. Some pools may offer aquatic accessories such as pull buoys, kickboards, flotation noodles, or water toys. Your Masters club may have its own supply of workout aids available to its members. If such gear exists at your facility, check whether you may use it during your workout. If equipment is not provided, you may be able to use your own buoys, boards, snorkels, etc., during specific workout sets. Ask your coach for clarification, including where such equipment should be placed during the workout to keep the deck from becoming unsafe with clutter.

- Your closest friends. I saved the best for last. When you join a Masters club and participate in USMS events, you’ll find a large and welcoming community of people who share your love of the water as well as your passion for health and fitness. Folks from all walks of life, endowed with a wide spectrum of abilities and interests, are all there to enhance their quality of life and a huge part of that is the camaraderie and friendship that grows organically when you share swimming as a common bond. Sure, there’s a lot to learn about pools, technique, competition, and terminology. It can be confusing and intimidating at first. But stick with it for a while and you’ll forge lifelong friendships, become part of something special, and find exciting new avenues toward personal growth.

See you at the pool!

—TERRY HEGGY

My parents tried to raise me with good social skills and proper manners, but as I’ve emphatically demonstrated with my back-to-breast IM transitions, there are some habits I can’t develop despite the best efforts of well-intentioned instructors. The same applies to my etiquette at the dinner table. I’m still unsure what to do with the various silverware you find at fancy restaurants since my only tools for dining at home are a plastic souvenir cup from a baseball game, my fingers, and a sturdy spork I found at a yard sale.

Although proper table manners remain firmly beyond my grasp, the rules of swimming etiquette are near and dear to my heart. I want everyone to enjoy their swimming experience, whether it’s lap swimming alone or working out with the friendly folks in your local Masters club. If all swimmers follow these simple guidelines, everyone will be able to have a great swim experience every time they enter the water.

Some of these swimming etiquette rules are universal, but some (such as lane management) vary from program to program. If you’re new to a facility or program, please ask for guidance when you arrive. If there’s a coach on deck, introduce yourself and ask for instructions. If there’s no coach, consult a facility staff member.

Many of swimming’s etiquette rules are based on common sense and respect for others. Everyone should be able to swim safely, have fun, and receive all the health and social benefits the sport provides. So, the No. 1 rule is to not be a jerk. Treat others the way you would want to be treated.

Health and Safety First

Before you enter the pool, familiarize yourself with the rules at the facility and follow them. Follow instructions from lifeguards and coaches and keep your eyes open for hazards as you swim.

- If you’re sick, stay home. If you’re sneezing or coughing, please do not swim with others. If you don’t feel well, it’s best to stay home and recover.

- Practice good hygiene. Shower before entering the pool. Use the designated restroom facilities as needed. And yeah, that means get out of the pool and head to the toilet if you get the urge to go during your swim.

- Communicate special needs. If you have special needs or health considerations (disability/impairment, injury, heart condition, potential need for medication during your swim, etc.), please notify the coach. If you’re fearful or unsure of your ability to finish a length, you may ask to be in a lane next to the wall. If you know you’ll need frequent breaks, look for a lane with an easily accessible way to exit.

- Enter with caution. Check carefully to ensure that no one is approaching and that you have clear water for entry. Enter the water feet first, from a seated position on the wall, ensuring that you don’t interfere with anyone else’s swim. If you enter a competition, read the additional info about warming up at meets.

- Avoid collisions. Maintain constant awareness of the lane lines and other markings or indicators, such as backstroke flags, to prevent accidentally running into the wall, the lane lines, or worst of all, another swimmer. This is especially important during backstroke, in which collisions are most likely to occur. Always pay attention to the position of other swimmers in your lane and steer clear of them.

Consideration and Respect

When you’re ready to enter the pool, the first thing is to choose an appropriate lane. If it’s your first Masters workout, just ask the coach where to go. Describe what you know about your experience, speed, and stroke preferences to help with the decision. If it’s lap swim, the traditional advice is to look for someone with nearly equal ability.

Another option that might work is to scan the pool for the best swimmer you can find, because experienced swimmers are used to swimming with others in their lane and more adept at avoiding collisions.

Look for an opportunity to let other swimmers in the lane you choose anticipate your entry without interrupting their workout. Ease into the water at the end of the lane and wait there in the corner until they notice your presence.

Circle swimming vs. splitting the lane

If there are more than two swimmers in a lane, swimmers all follow in sequence in a counterclockwise loop around the lane, AKA circle swimming. There are two variations, both with swimmers staying to the right side of the lane stripe, as indicated in Lanes 1 and 2. Like driving, you keep to the right.

Swimmers typically leave the wall five seconds after the swimmer before them. In a long-course pool, 10 seconds is common. Ask your coach and/or lanemates which pattern and which send-off are standard at your workouts.

In the Lane 1 example, swimmer 1 swims the first length with other swimmers following, then cuts to the opposite (left) corner to execute the turn (which leaves room on the wall for swimmer 2 if they’re following closely). After the turn, the lead swimmer continues, keeping to the right side of the lane stripe with other swimmers continuing to follow.

In the Lane 2 example, the swimmers are making the same circles but turning at the center of the lane rather than the far-left side. The lead swimmer veers toward the center when approaching the wall, turns on the cross, and pushes off toward the right when leaving the wall.

If there are only two swimmers in a lane, you may be able to split the lane (Lane 3). When splitting, each swimmer swims straight down and back on a single side of the lane, never crossing the lane stripe, keeping near the rope or wall when the other swimmer passes. Splitting works best when swimmers are not side by side, so again, a staggered start time is recommended. Ask your coach for advice if any problems arise.

Additional etiquette for a Masters workout

The following rules are widely adopted, but individual clubs or facilities might modify or replace them to serve their specific needs, so check with your coach or facility staff to be sure.

- Arrive early enough to be in the water when a workout begins. Late arrivals disrupt other swimmers and may cause lane shuffling, which is a pain for everyone.

- Don’t interrupt other swimmers when they’re swimming. Save socializing for rest breaks, as well as for before and after the workout. If you have questions, please ask the coach.

- Listen when the coach is talking. This helps everyone (including yourself) have the best chance to understand what the coach expects from the upcoming set. If you still don’t understand when the coach finishes, ask for clarification.

- Line up appropriately. If your lane is circle swimming, assume your proper position in the swim order. The fastest swimmer should go first, and the slowest should go last. Remember that relative speeds can be different on different days and with different strokes, so determine your position based on what’s happening now, not on your ego’s shining memory of your glory days.

- Modify sets as needed based on your experience, fitness, and needs. Masters swimming is for you, so if you need to take extra breaks, switch strokes, or get out early, just do so. Just be respectful of the other swimmers and avoid disrupting the workout for others.

- Respect your teammates. In addition to the lane management rules below, consider how you can be the swimmer everyone wants to share a lane with. This includes the obvious things of being welcoming and nice but also things like brushing your teeth, avoiding fragrances, keeping your nails trimmed to avoid scratching anyone in a crowded lane, etc.

- Minimize your footprint. If your lane is crowded, make room for other swimmers. Turn sideways to take up less wall space between repeats, get out if you’re taking a long break, etc. If you have equipment on deck (fins, paddles, water bottles, etc.), leave room for gear that belongs to your lanemates.

- Set an example. Encourage and support your teammates. Acknowledge great performances and share in the joy when your friends are having fun. Unless you have a prior arrangement, it’s usually best to leave critiques to the coach. If you spot another athlete displaying a technique flaw, for example, the best approach is to privately mention it to the coach, who can then pass a corrective tip along to the swimmer.

- Learn the lingo. When you first join a swim club, you’ll hear a ton of terms that mean something specific in the sport. Don’t freak out about it; they’ll begin to make sense quickly. If you hear something that you don’t understand, ask a teammate or coach to bring you up to speed. You’ll be a pro within a few weeks!

Traffic management

These tips help a crowded lane run smoothly by minimizing collisions and road rage.

- Start and finish at the wall. Don’t stop in the middle of the pool or at the backstroke flags. When waiting between sets, the current lane leader should stand sideways against the right-side lane line (the left as swimmer come into the wall or right as they push off for their next swim) to leave room for other swimmers to touch the wall and have room to prepare for the next repeat.

- Leave at your appropriate send-off. For sets on a specific interval, the lane leader is responsible for tracking the send-off times, and subsequent swimmers generally leave on 5- or 10-second increments after the leader departs.

- Learn to swim streamlined. Presenting a narrow profile in the water makes you go faster, but it also helps reduce the space you take up as you zip down the lane.

- Deal with drafting. If one swimmer follows another very closely, the follower gains a speed advantage from the leader’s slipstream. This is known as drafting, and it can make a significant difference in speed. Following closely does risk the unintentional tapping of the leader’s toes, which some people find annoying. An unintentional tap also risks sending the “I’m ready to pass” message (see passing etiquette below). In addition, the leader may become resentful from feeling that they’re doing more work (which they are). On the other hand, some people don’t mind drafting at a workout. Ask the person you’re following if they mind, and if they do, either back off or offer to go ahead and take the lead yourself.

- Pay attention to the flow of traffic, especially when non-freestyle strokes are being swum. If you consistently know where everyone is in your lane, you’ll be able to adapt your stroke and lane position to avoid collisions, as well as being prepared to deal with passing situations (see below). When two swimmers doing different strokes approach each other on opposite sides of the lane, the swimmer doing the stroke that’s easier to modify should adapt what they’re doing to ensure a safe crossing. The order of precedence for such drive-by encounters is backstroke (because they can’t see you coming), then butterfly, breaststroke, freestyle, and kicking/drills. For example, a freestyler would watch out for and avoid anyone swimming back, fly, or breast.

Passing etiquette

When swimming circles for longer sets, at some point one swimmer will want to pass another. Here’s how that can be done smoothly:

- Gently tap the foot of the person you want to pass. If there’s room, pass them to the inside of the lane. If there’s oncoming traffic, wait until the person pulls over at the end of the lane and then go around. If you tap accidentally, back off so that the person knows they should continue to lead and so that you won’t repeat the unintentional signal.

- Yield to faster swimmers. Pay attention to your lanemates so that you always know where everyone is and when someone is coming up behind you. When a faster swimmer approaches and taps your feet, pull over to the outside of the lane, then stop at the wall if necessary to let them pass.

- Modify your departures. If a faster swimmer is approaching to do a turn when you are about to leave on an interval, wait until they have gone by and then start. If a slower swimmer is approaching to do a turn as you prepare to leave on an interval, cut your rest short and leave before they get there.

- Finish at the wall. When you complete a repeat, pull over to the right side of the lane to let others turn or finish. Turn sideways and hold the wall with only one hand so you’ll take up less space. If there are several people in the lane, those on either end of the queue can move away from the wall, staying against the lane line.

Recognize reality

Despite our best efforts to secure smooth swimming via proper etiquette, a crowded lane is occasionally bound to experience a bit of chaos. Arms cross over lane lines, turns go sideways, and intervals are forgotten in the fog of fatigue. Accept these anomalies with humor and dignity. If each of us does our best to respect and support fellow swimmers with encouragement, recognition, and cheerful enthusiasm, then we’ll continue to epitomize the spirit of Masters Swimming.

—TERRY HEGGY

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

Swimming is one of the best forms of exercise you can do, but don’t just take our word for it. Here are four reasons why you should be getting in the water if you want to get in shape and stay fit.

1. Swimming Keeps You Going

The most common New Year’s resolutions include becoming healthier and exercising more, but about 80 percent of these goals fall through by February, according to U.S. News & World Report.

Swimming might be the best way for these goal-setters to stay on their targets.

“The enjoyment in activity is extremely important in terms of continuing to engage in those activities,” says Hirofumi Tanaka, a professor in the University of Texas’s Department of Kinesiology and Health Education.

Tanaka points to a study of minimally to moderately obese young women done by Grant Gwinup and published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine in 1987. Participants reported that they enjoyed swimming much more than running and cycling.

Swimming is also the third-most popular exercise, according to the most recent data available from the U.S. Census Bureau, meaning you’ll also have someone to work out with.

2. Swimming’s Easy on Your Body

Let’s face it: Jumping into the pool at 6 a.m. each day might not be the most fun you’ll ever have. But the fact that you’re getting into water is one of the best parts of being a swimmer.

“In swimming, you are floating, so there are no joint forces,” says Tanaka, who bikes, runs, and swims. “The impact is much smaller than when you’re running.”

Swimming’s biggest benefits come later in life, when adults may be carrying a few extra pounds because of a slowed metabolism or less time to exercise because of the time demands of their job or family. The extra weight places more pressure on joints while exercising.

Tanaka adds that exercising in water also appears to be the best thing for people with arthritis.

“Every time you move, your joints, you experience those joint pains,” Tanaka says. “Swimming in a sense is an extremely good form of exercise for that.”

3. Swimming Can Slow Down the Aging Process

David Tanner was taken aback when he participated in his first Masters swim meet at age 29 in 1979. He hadn’t expected the older swimmers to be as boisterous as they were, but some relay teams were so excited that he thought they resembled swimmers less than half their age.

Tanner, who largely works with graduate students in Indiana University’s School of Public Health after swimming for Indiana from 1968–72, now knows that swimming helps make people younger—in a sense.

Tanner and Joel Stager, the director for the Counsilman Center for the Science of Swimming at Indiana, referenced a series of studies produced by Indiana graduate students that found Masters swimmers can have a biological age about 20 years younger than their chronological age if they swim at least an hour a day five times a week. But Stager said the studies are still ongoing.

“With intense training, you can maintain, but you have to be pretty serious about it,” Tanner says. “You can maintain up until the age of 70. After 70, time starts to weigh.”

4. Swimming Makes You Feel Better

You can find discussion of “runner’s high” easily, but what about “swimming high?” It may not be called that, but Tanaka has found evidence of swimming’s mental benefits.

Tanaka examined people who had stage 1 or stage 2 essential hypertension in a study published in August 1999 in the Japanese Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine. The participants completed a questionnaire designed to measure their mood, went through either a 10-week swimming program or didn’t exercise, and then took the questionnaire again.

Tanaka found that the participants who went through the swimming routine received a higher vigor-activity score, which “represents a mood of vigorousness, ebullience, and high energy, which are some of the central components of health-related quality of life,” Tanaka wrote.

His study also found the people who swam reduced their anger and fatigue scores from the first questionnaire to the second questionnaire by 34% and 28%, respectively.

—DANIEL PAULLING

From tiny summer league competitions to the Olympic Games, meets for swimmers at all stages and levels of speed and skill development abound. These days, swimmers from the youngest kids to the oldest Masters swimmers have many options to test their skills and work their way up the ladder to ever bigger competitions.

Here are some of the biggest swimming events that attract the best athletes in the sport today.

Olympic and Paralympic Games

The swimming events at the Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games are among the most prestigious competitions in the world. Often referred to as the sport’s biggest, brightest stage, the Olympic and Paralympic Games take place once every four years, and swimming is one of the most-watched sports.

One of the oldest sports in the modern Olympics, swimming has been featured at the Games since the first Olympiad held in Athens in 1896. In Paris 2024, more than 850 athletes will compete for medals in 35 events ranging from 50 to 1500 meters in the pool and the 10-kilometer open water race. The Paralympic program is slightly different, but also offers a range of distances from 50 meters to 10K, along with various classifications related to competitors’ level of disability.

Olympic and Paralympic Trials

Before athletes arrive at the Olympic or Paralympic Games, they must first qualify for the team in their own country. These squads are often determined based on national-level competitions called the Olympic and Paralympic Trials hosted by some (but not all) countries that send a team. In some countries, like the United States, these meets feature some of the best and fastest racing you’ll find anywhere in the world, on par with the Olympic and Paralympic Games themselves.

World Aquatics Championships

Organized by World Aquatics (formerly known as FINA, the Fédération Internationale de Natation), these championships are held every two years and feature swimming events alongside other aquatic disciplines such as diving, water polo, synchronized swimming, and open water swimming.

Masters World Championships are also held around the same time, usually in the same venue as the world championships events. It’s a great way to make new Masters friends from other countries and get to travel and experience the excitement of a world championship meet.

LEN European Aquatics Championships

Hosted by Ligue Européenne de Natation (LEN), the European Championships got their start in 1926 and are held every two years in even years. This long course meters event, which like the Olympics moves to a different city with each iteration, brings together top swimmers from European nations.

Pan Pacific Swimming Championships

This major international swimming competition takes place every two years and involves countries from the Pacific Rim, including the United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan. Launched in 1985, Pan-Pacs is a long course meet modeled after the European Championships for countries that weren’t eligible to swim in the Euro Championships.

World Aquatics Swimming Championships (Short Course)

Also referred to as short course worlds, this meet launched in 1993 and takes place every two years. It’s held in a 25-meter pool, unlike the traditional 50-meter pool used in Olympic events, and is typically staged in December.

Other Multisport Events

Swimming is a prominent sport in various multisport events where multiple disciplines are showcased. Some additional important swimming competitions are held as part of the following large, multisport events around the world:

- African Games. Formerly called the All-Africa Games or the Pan African Games, this all-continent multisport event is held every four years and is organized by the African Union with the Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa and the Association of African Sports Confederations.

- Asian Games. Also known as Asiad, the Asian Games are held every four years and attract athletes from all across Asia. They were launched in 1951 and since 1982, they have been organized by the Olympic Council of Asia. This competition is recognized by the International Olympic Committee and is the second-largest multisport event after the Olympic Games.

- Commonwealth Games. This event takes place every four years and draws athletes from the Commonwealth of Nations, which consists of states and territories that were formerly part of the British Empire.

- FISU World University Games. This event is staged every two years in a different city as a celebration of international university sports and culture.

- Mediterranean Games. This multisport event is organized by the International Committee of Mediterranean Games and is held every four years. It draws athletes from countries that border the Mediterranean Sea.

- Pacific Games. First staged in 1963 and then called the South Pacific Games, the Pacific Games is a continental multisport event held every four years that draws competitors from across Oceania.

Biggest Masters Competitions

There are many masters competitions in the United States and abroad.

- USMS pool national championships. U.S. Masters Swimming hosts a Spring National Championship and Summer National Championship every year. The spring meet, usually in late April or early May, draws about 2,000 swimmers, and the summer meet, usually in early August, draws about 1,000 swimmers. Both of these meets travel around the country.

- USMS open water national championships. USMS hosts up to six open water national championships a year. These usually happen in the summer across the country.

- UANA Pan American Championships. The UANA Pan American Championships take place every two years, in even years, throughout North and South America.

- IGLA Championships. International Gay & Lesbian Aquatics stages championship swim meets every year.

- Gay Games. This international sporting event takes place every four years.

—ELAINE K. HOWLEY

Want Swimming Tips in Your Inbox?

Input your email below to get great swimming articles, videos, and tips sent to you monthly. (USMS members already get it)

Thanks! We just sent you your first email and will you should receive at least one monthly.

This is part one of our four-part Swimming 101 guide. The other three parts are linked below when you're ready for them.